Some photos from the Conference are presented below. To see the abstracts and poster, see: 2017 Massachusetts Undergraduate Research Conference.

Some photos from the Conference are presented below. To see the abstracts and poster, see: 2017 Massachusetts Undergraduate Research Conference.

=================================================

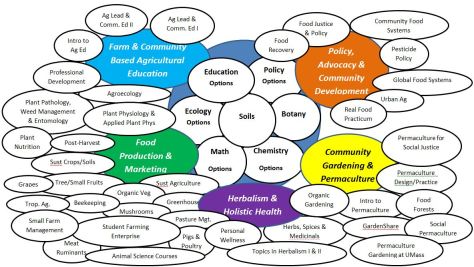

Sustainable Food and Farming students study botany, soils, ecology, chemistry, math, public policy and agricultural education. And so much more!

By Wayne Roberts

Earth Day has long been a day to celebrate joy in our relations with the earth, a nd renew commitments to do our personal best to respect the Earth’s needs and act on our ability to protect the planet.

nd renew commitments to do our personal best to respect the Earth’s needs and act on our ability to protect the planet.

In that vein, I want to introduce you to an article on researching food system agendas; it just came out in the April edition of a journal called Food Security. I think it’s game-changing for professional practitioners, citizen activists and young people looking for a career path in the food sector, as well as the target audience of academic researchers.

My comments below aren’t a substitute for reading the article, which is an easy read. I

My comments below aren’t a substitute for reading the article, which is an easy read. I

Join UMass Sustainable Food and Farming for a FREE and public screening of the short documentary “Brooklyn Farmer” which tells the story of Brooklyn Grange, a group of urban farmers who endeavor to run a commercially viable farm in New York City.

The film will be followed by a panel discussion with Dana Lucas (Freight Farms Boston and UMass Hydroponics) & Frank Mangan (UMass Professor of Urban Farming).

The film will be held in

Synopsis of the Film:

“Brooklyn Farmer” explores the unique challenges facing Brooklyn Grange, a group of urban farmers who endeavor to run a commercially viable farm within the landscape of New York City. The film follows Head Farmer Ben Flanner, CEO Gwen Schantz, Communications Director Anastasia Plakias, Farm Manager Michael Meier, and Beekeeper Chase Emmons as their growing operation expands from Long Island City, Queens to a second roof in the Brooklyn Navy Yards. The team confronts the realities inherent in operating the world’s largest rooftop farm in one of the world’s biggest cities.

Panelists:

Frank Mangan

A focus of my program has been to evaluate production and marketing systems for vegetable and herb crops, with an emphasis on crops popular among immigrant communities. Since 2003, farmers in Massachusetts made more than five million dollars in retail sales of crops introduced from my program, crops that had not been grown in Massachusetts before. A majority of the research done by my program is at the UMass Research Farm in Deerfield MA. We also evaluate practical postharvest and pest management strategies for these new crops. Our program works closely with nutritionists at UMass to provide nutritionally balanced and culturally-appropriate recipes for these immigrant groups. This webpage provides information on the crops evaluated and introduced by my program: http://www.worldcrops.org/

A focus of my program has been to evaluate production and marketing systems for vegetable and herb crops, with an emphasis on crops popular among immigrant communities. Since 2003, farmers in Massachusetts made more than five million dollars in retail sales of crops introduced from my program, crops that had not been grown in Massachusetts before. A majority of the research done by my program is at the UMass Research Farm in Deerfield MA. We also evaluate practical postharvest and pest management strategies for these new crops. Our program works closely with nutritionists at UMass to provide nutritionally balanced and culturally-appropriate recipes for these immigrant groups. This webpage provides information on the crops evaluated and introduced by my program: http://www.worldcrops.org/

Starting in 2011, we have begun to work with urban growers as part of an overall systems approach to provide fresh produce to urban populations. As part of this work we’re also evaluating the carbon footprint used to produce and transport fresh produce to urban settings. We have created a Facebook page to report on this work: https://www.facebook.com/umassurbanag

Dana Lucas

I am from a city and I cherish local food. I have found this appreciation for sustainable produce to be extremely helpful in my own personal development within controlled environmental agriculture.

I work for an urban farm that owns three Freight Farms. I have learned to successfully manage and market almost five acres of hydroponic produce. I also have recently created my own company for urban farm consulting. I design and build hydroponic systems for commercial and residential spaces around Boston, MA. I am most proud of recently receiving a grant to build and design a vertical farm on campus at UMass Amherst, which will provide hydroponic produce to dining halls on campus starting this winter.

I believe the further expansion of city farms will help to give urbanites the opportunity to experience food systems more accessible. Completing my education in agriculture is extremely exciting and important for my career and our world’s future sustainability. I believe that urban agriculture will have a great influence on social, economic, and resource consumption problems.

If you look out of the campus-side windows in Franklin Dining Commons after the sun has gone down, you can see a mix of white, blue and magenta lights illuminating the inside of the Clark Hall Greenhouse.

These lights mark the home of the UMass Hydroponics Farm Plan, where Dana Lucas, a junior sustainable food and farming major, and Evan Chakrin, a nontraditional student in the Stockbridge School of Agriculture, have been working throughout the winter growing fresh leafy greens.

Back in December, the duo received a $5,000 grant from the Stockbridge School of Agriculture to grow produce year-round on an on-campus hydroponic farm. Hydroponics, a method of farming with water and nutrients in place of soil, allows for a continual harvesting cycle.

Along with limited pesticide use and saving 90 percent more water than a traditional farm, the farm will produce approximately 70 heads of lettuce a week, every week of the year. Lucas and Chakrin emphasize the importance of this perpetual cycle in meeting the University’s sustainability efforts.

Along with limited pesticide use and saving 90 percent more water than a traditional farm, the farm will produce approximately 70 heads of lettuce a week, every week of the year. Lucas and Chakrin emphasize the importance of this perpetual cycle in meeting the University’s sustainability efforts.

On the University of Massachusetts website, it states, “The University recognizes its responsibility to be a leader in sustainable development and education for the community, state and nation.”

“I don’t know how we can say our food is sustainable at UMass if it’s only grown 10 weeks of the year in New England,” Lucas said.

The location allows UMass Hydro to get their greens across campus by either walking, biking or driving short distances, leaving almost no carbon footprint.

“I think this is something that really excites me and Evan because we really see a demand for fresh, local food and this is a way to actually fulfill it,” Lucas said.

Although the farm’s production capacity cannot currently meet the needs of the dining halls, Lucas and Chakrin are looking into alternative options to get their greens on the plates of students.

“We’re kind of just centering on student businesses right now because they’re smaller and they’re run by our friends, so we can easily get into the market,” Lucas said.

“We’re kind of just centering on student businesses right now because they’re smaller and they’re run by our friends, so we can easily get into the market,” Lucas said.

Their first official account is with Greeno Sub Shop in Central Residential Area.

Last week, Greeno’s hosted a special where UMass Hydro’s microgreens were free to add to any menu item.

In a statement posted to their Facebook page, they stated, “One of the goals of our mission statement is to source locally whenever possible, with UMass Hydro right down the hill, this is almost as fresh as it can get.”

Chakrin and Lucas are currently working on getting their greens served at other on-campus eateries.

In addition to adding more accounts, there is a strong focus on getting other students interested in the emerging field of hydroponics.

“We can use this as a teaching facility for students. The techniques we’re using are used in multi-acre industrial greenhouses for lettuce, so we could scale right up potentially,” Chakrin said.

The two are hoping to work UMass Hydro into the curriculum in Stockbridge, allowing students to work hands-on with the systems while also earning credits.

“Maybe we can do a one credit, half semester thing or something,” said Chakrin.

“There has been some discussion about having an accredited course for next fall where we can teach what I’m assuming are mostly going to be Stockbridge students, but we’re open to anybody and everyone who’s interested in getting involved with hydroponics,” Lucas said.

“There has been some discussion about having an accredited course for next fall where we can teach what I’m assuming are mostly going to be Stockbridge students, but we’re open to anybody and everyone who’s interested in getting involved with hydroponics,” Lucas said.

The grant covered the cost of seeds, equipment and other miscellaneous items like scissors, but the responsibility of building the farm fell entirely on Lucas and Chakrin.

“It felt really cool that we were given this much responsibility I feel like, to just buy the stuff and then build it,” Lucas said.

Chakrin noted how one of the biggest obstacles faced in getting the project off the ground was finding an available space on campus.

“Initially we were just asking for a 10-by-10 closet somewhere, then Stockbridge professor , Dr. Dan Cooley, was like ‘Do you think this greenhouse will work?’ and we were like ‘Of course!’” Chakrin said.

“He kind of posed it as a bummer that we weren’t going to be in a closet and we were like ‘No, no, no that’s fine!’” Lucas said, laughing.

“Without the space, none of it would be possible, so being allowed to use this space is just huge and we’re so lucky to have that,” Chakrin said.

The students also expressed appreciation to Dr. Daniel Cooley, who sponsored the project and Dr. Stephen Herbert for his support and donation of supplies.

Out of the entire space granted to UMass Hydro, only a portion of it is currently being used. In order to make use of the underutilized space, Chakrin and Lucas are hoping the future of UMass Hydro involves more funding.

“We want to see Dutch buckets and a vertical system in here so we can show students the breadth of what you can do with hydroponics,” Lucas said.

Visitors are encouraged to stop by at the Clark Hall Greenhouse on Tuesdays between 3 p.m. and 7 p.m. And you can follow the project on Facebook at UMass Hydro!

Callie Hansson can be reached at chansson@umass.edu.

We know that many UMass students find themselves dissatisfied with their major in their first or second year of college. If this is true for you…. it is not too late to change!

UMass Sustainable Food and Farming (SFF) is hosting a three part PUBLIC and FREE film series to provide a community space where students can critically engage in issues surrounding the food system. Each film is followed by a panel discussion featuring local individuals within the field.

On March 9th, 6-8pm in the W.E.B Dubois Library, Floor 19 Room 1920, SFF will be screening the documentary “Seeds of Time” followed by a panelist discussion at 7:30pm featuring professor of Economics, James Boyce, along with other individuals from the community.

On March 9th, 6-8pm in the W.E.B Dubois Library, Floor 19 Room 1920, SFF will be screening the documentary “Seeds of Time” followed by a panelist discussion at 7:30pm featuring professor of Economics, James Boyce, along with other individuals from the community.

Film Synopsis

A perfect storm is brewing as agriculture pioneer Cary Fowler races against time to protect the future of our food. Seed banks around the world are crumbling, crop failures are producing starvation and rioting, and the accelerating effects of climate change are affecting farmers globally. Communities of indigenous Peruvian farmers are already suffering those effects, as they try desperately to save over 1,500 varieties of native potato in their fields. But with little time to waste, both Fowler and the farmers embark on passionate and personal journeys that may save the one resource we cannot live without: our seeds.

10,000 years ago the biggest revolution in human history occurred: we became agrarians. We ceased hunting and gathering and began to farm, breeding and domesticating plants that have resulted in the crops we eat today. But the genetic diversity of these domesticated crops, which were developed over millennia, is vanishing today. And the consequences of this loss could be dire.

As the production of high yielding, uniform varieties has increased, diversity has declined. For example, in U.S. vegetable crops we now have less than seven percent of the diversity that existed just a century ago. We are confronted with the global pressures of feeding a growing population, in a time when staple crops face new threats from disease and changing climates.

Crop diversity pioneer Cary Fowler travels the world, educating the public about the dire consequences of our inaction. Along with his team at The Global Crop Diversity Trust in Rome, Cary struggles to re-invent a global food system so that it can, in his words: “last forever.” Cary aims to safeguard the last place that much of our diversity is left in tact: in the world’s vulnerable gene banks.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, a group of indigenous Peruvian farmers work to preserve over 1,500 native varieties of potato in their fields. Through the guidance of activist Alejandro Argumedo and the help of the International Potato Center gene bank in Lima, several communities join forces to create a new conservation grounds called “The Potato Park.”

But not all is well in this haven for diversity. The Andes Mountains, our planet’s most diverse region for potatoes, is already seeing the crippling effects of climate change. Potato production has risen more than 500 feet in altitude over the last 30 years, leaving varieties at lower elevations unable to produce. With erratic weather patterns already eroding biodiversity, what is to be done when these farmers can no longer continue moving “up”?

With a passion few possess, Cary set out to build the world’s first global seed vault – a seed collection on a scale larger than any other. The vault, located in Norway, is an unprecedented insurance policy for the crop diversity of the world. In an extraordinary gesture of support, the farmers of the Potato Park become the first indigenous community to send samples of their potato diversity to the vault for safekeeping.

But as the stakes of maintaining a secure global food system continue to rise, adaptation will become a requisite for our own survival. How can we best maintain the diversity that still exists for our food crops? How do we create new diversity to adapt our fields to a changing climate? The answers are as complex as the system they intend to fix. And it will require a combination of efforts: from scientists, plant breeders, researchers, farmers, politicians, and even gardeners.

PLEASE SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS/REFLECTIONS IN THE COMMENTS BOX BELOW

STOCKSCH 197 W: How to Recover a Truly Sustainable Food System:

A Look at Food Waste and Recovery

Instructors:

Class Meeting: Tuesday 4:00-5:15 pm

Location: Paige Lab Conference Room (202)

Office Hours: By appointment

Contact Information:

Course Description:

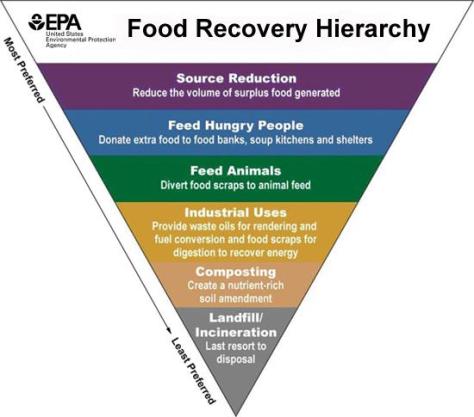

This course is an introduction to food waste, and the impact waste has on our food system. We will introduces the current food recovery hierarchy, and examines how consumers, producers and distributors waste food. We will explore the environmental and social impact of food waste in our food system, and introduce social and policy initiatives employed to recover food. Students will read, reflect and discuss the actionable steps being taken to shift our local food system’s food waste into food recovery.

This course is an introduction to food waste, and the impact waste has on our food system. We will introduces the current food recovery hierarchy, and examines how consumers, producers and distributors waste food. We will explore the environmental and social impact of food waste in our food system, and introduce social and policy initiatives employed to recover food. Students will read, reflect and discuss the actionable steps being taken to shift our local food system’s food waste into food recovery.

Prerequisites: Open to all UMass students interested in food recovery.

Required Course Materials:

A blank notebook should be brought to every class. This notebook will be used for notes, reflections and homework assignments. It is a vital part of your grade. Laptops will be permitted as a note taking tool ONLY if students elect to create a digital journal.

There will be no formal text book for this course, readings will be distributed via .pdf

Grading:

| Project | Percentage |

| Pre-Course Self Assessment | 10.00% |

| Reflection Journal:

· Interview Project · Case Study Notes · Weekly Homework · Technology Tools |

40.00% |

| Case Study Presentation | 40.00% |

| Post-Course Self Reflection | 10.00% |

Course Schedule:

In Class:

Review Syllabus

Based on current knowledge and assumptions students will build EPA Food Recovery Hierarchy in small groups

Self-Assessment Survey & Learning Styles Quiz

http://www.learning-styles-online.com/inventory/

Homework:

Read:

Do:

In Class:

A definition and discussion of the EPA Food Recovery Hierarchy

Review and discuss our class’s cumulative weekly food waste

Homework:

Read:

Do:

In Class:

Discuss readings from American Wasteland and the Economic Research Service

Think/Pair/Share Activity

Homework:

Read/Do:

In Class:

Facilitated discussion with student questions

Experiential Activity

Case Study Overview and Distribution

Homework:

Review assigned Case Study, record brainstorm and any actionable steps in your journal

In Class:

Interview Questions Brainstorm

Discussion about Farm-Based Food Waste

Homework:

Read:

Do:

In Class:

An introduction to food insecurity with facilitated discussion and student questions

Homework:

Read:

Do:

In Class:

Facilitated discussion with student questions

In-Class reading: Farmers Help Fight Food Waste by Donating Wholesome Food

http://blogs.usda.gov/2015/04/03/farmers-help-fight-food-waste_by-donating-wholesome-food/

Homework:

Read:

Do:

In Class:

Panel Discussion, guests TBD

Homework:

Read:

Do:

In Class:

How is food insecurity being addressed in our community?

Facilitated discussion with student questions

Facilitated review of results found in Interview Questions Project

Homework:

Read:

In Class:

Presentation by Mary Bell

Facilitated discussion with student questions

Homework:

Read:

Do:

In Class:

Discuss Mass Local Food Action Plan

Think/Pair/Share Activity

Homework:

Review:

In Class:

Students will complete a final self assessment

Students will complete an exit survey

Homework:

Meet with group to work on final presentations

In Class:

Final Presentations of Case Studies

Attendance at all presentations is mandatory to receive a passing grade

Assignments

| Project | Description | Due Date |

| Case Studies in Food Recovery

◦ A Perfect Loop – Food Recovery in San Diego, BioCycle 2013 ◦ The Good Food Fight for Good Samaritans: The History of Alleviating Liability and Equalizing Tax Incentives for Food Donors, Stacey H.Van Zuiden- 2012 Drake University ◦ 3rd Case Study TBD |

1. Students will review one of three case studies of a food recovery project in our local/regional food system assigned by instructors

2. Case studies are designed to address our three themes: farm/environmental impact, food security/food justice, and food policy 3. Students will record main ideas from the reading in their reflection journal 4. Students will generate a list of 3-5 ideas for addressing the thematic nature of the case study and record them in the reflection journal 5. Students will work in small groups assigned by instructors 6. Using case studies students will generate an actionable idea for addressing food waste and recovery at a campus, local or regional level 7. Students will prepare a presentation of their main ideas and actionable steps to address food waste using Prezi or Power Point |

5/2/17

5/9/17 |

| Interview Project | 1. As a class students will compile interview questions

2. Instructors will generate a survey based on student input and distribute digitally via Google Forms 3. Students will interview 3 people in their communities about their food system experience: one consumer, one producer, one retailer or distributor 4. Students will reflect on their findings in reflection journal 5. Findings will be shared in class and discussed |

03/28/17 |

| Reflection Journal | 1. All weekly reflections and writing assignments MUST be kept in one reflection journal

2. The journal will be collected on the last day of class |

04/25/17 |

Course Policies

While it is true that the Stockbridge School of Agriculture has been offering courses in food production and marketing since the beginning, our students today are engaged in many learning activities that include farming but also focus on necessary changes to the larger food system.

Here are a few of the things Stockbridge and other UMass students have been up to in October….

American food writer MFK Fisher once said, “First we eat, then we do everything else.” Food is central to so much in our lives – family, health and community. But what about the food we don’t eat?

More than a billion tons of food is never consumed by people; that’s equivalent to one-third of all food the world produces. What many people may not know is that one in nine people on earth don’t have enough food to lead an active life, or that food loss and waste costs the global economy $940 billion each year, an amount close to what the entire UK government will spend in 2016.

They may also not know the incredible effect food loss and waste has on the environment. Eight percent of the greenhouse gases heating the planet are caused by food loss and waste. At the same time, food that’s harvested but lost or wasted uses 25 percent of water used in agriculture and requires cropland the size of China to be grown. What an incredibly inefficient use of precious natural resources.

When you look at the kind of impact food loss and waste has on our environment, economy and society, it’s clear why the United Nations included it among the most urgent global challenges the Sustainable Development Goals would address. Target 12.3 [2] of the goals calls for nations to “halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses” by 2030. It’s certainly an ambitious challenge, but it is also one that’s achievable.

This week is Climate Week, an opportunity to take stock of where we are on critical environmental issues like food loss and waste. A new report [3] on behalf of Champions 12.3 [4] – a unique coalition of leaders across government, business and civil society who are dedicated to achieving Target 12.3 – assesses our progress so far.

The report details a number of notable steps that have happened around the world, including national food loss and waste reduction targets established in the United States and in countries across the European Union and African Union.

It also highlights efforts to help governments and companies measure food loss and waste, such as the FLW Standard [5] announced in June, and new funding like the Danish government’s subsidy program and The Rockefeller Foundation’s Yieldwise [6], a $130 million investment toward practical approaches to reducing food loss and waste in Kenya, Tanzania, Nigeria, the United States and Europe. There have also been advances in policies as well as education efforts like the Save the Food [7] campaign to raise awareness of food loss and waste.

The progress is promising. But the report also notes that the action does not yet match the scale of the problem, and much more work is needed worldwide if we are to successfully meet Target 12.3 in just 14 short years.

Food waste can be turned into organic fertilizer. (Flickr/EarthFix)

Food waste can be turned into organic fertilizer. (Flickr/EarthFix)

While the magnitude of the food loss and waste challenge can seem daunting, I know from my own experience in the United Kingdom [8] that progress can be made if you have the right levels of engagement and commitment, and an understanding of the size of the problem and where to focus. In a period of five years, we managed to reduce household food waste across the UK by 21 percent. It’s an impressive figure, but there is still so much more to do!

The immediate question is, how can leaders accelerate progress? Every government, city and business involved with food must set reduction targets, measure food loss and waste in their borders or supply chains, and act to reduce such waste. Here’s why:

Measuring food loss and waste also helps make the impacts more tangible. Throughout the employee line and within households, there is just not enough awareness of the issue generally, nor its implications for wasted money, wasted resources and wasted opportunity.

If the world can pay as much attention to all the food we don’t eat as to the great culinary trends of the day, we will build a food future that can sustain generations to come. I’m optimistic that we will achieve this. It won’t be easy, but the stakes are too high to miss our chance to create monumental change.

Links

[1] http://www.wri.org/profile/elizabeth-goodwin

[2] http://indicators.report/targets/12-3/

[3] http://www.champions123.org/2016-progress-report

[4] https://champions123.org/

[5] http://flwprotocol.org/

[6] https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/our-work/initiatives/yieldwise/

[7] http://www.save-food.org/

[8] http://www.wrap.org.uk/blog/2016/03/root-uk%E2%80%99s-food-waste-success-story-courtauld