by Jonathan Latham, PhD

In 1381, for the first and only time, the dreaded Tower of London was captured from the King of England. The forces that seized it did not belong to a foreign power; nor were they rebellious workers – they were peasants who went on to behead the Lord Chancellor and the Archbishop of Canterbury who were, after the king, the country’s leading figures. A tad more recently, in the U.S. presidential election of 1892 a radical populist movement campaigned for wealth redistribution and profound economic reform. The populists won five states. All of them were rural.

Descent from such rebels is typically claimed by unions and groups on the political left; but, over the long run of history, the most effective opponents of excessive wealth and privilege have not normally been city dwellers, workers or unions. Instead, they have usually been those with close links to food and the land, what we would now identify as the food movement.

Even today, in more than a few countries, food is the organising principle behind the main challengers of existing power structures. In El Salvador, the National Coordinator of its Organic Agriculture Movement is Miguel Ramirez who recently explained:

We say that every square meter of land that is worked with agro-ecology is a liberated square meter. We see it as a tool to transform farmers’ social and economic conditions. We see it as a tool of liberation from the unsustainable capitalist agricultural model that oppresses farmers.

The Salvadoran Organic Agriculture Movement wants much more than improved farming. It is seeking enhanced political rights, long term ecological sustainability, social equity, and popular health. Ramirez calls it “this titanic but beautiful struggle, to reclaim the lives of all Salvadorans“.

They may be small farmers, but they have a grand ambition that is even shared worldwide. But, how realistic is it? Could the food movement be the missing vehicle for transformative social change?

The question is timely. Not long ago, the New York Times asserted that the centre aisles of US supermarkets are being called “the morgue” because sales of junk food are crashing; meanwhile, an international consultant told Bloomberg magazine that “there’s complete paranoia“, at major food companies where the food movement is being taken very seriously.

The context of that paranoia is that food movements are rapidly growing social and political phenomena almost all over the world. In the US alone, there have been surges of interest in heirloom seeds, in craft beers, in traditional bread and baking, in the demand for city garden plots, in organic food, and in opposition to GMOs. Simultaneously, there has been a massive growth of interest in food on social media and the initiation or renewal of institutions such as SlowFood USA and the Grange movement, to name just a few.

Even at the normally much quieter farming end of the food value chain, agribusiness has had to resort to buying up “independent” academics and social media supporters to boost the case for GMOs and pesticides.

So whereas not so very long ago food, and even more so agriculture, were painfully unfashionable subjects, all of a sudden, individuals all over the globe have developed an often passionate interest in the products and processes of the food system.

If food regime change is in the air, the questions are: Why? Why now? And the big one: How far will it go?

The direction of the food movement

The answer to these questions comes into focus if we analyse the food movement from the perspective of five different “puzzle pieces”. If we do that we can see that there are profound reasons why the food movement is succeeding and growing.

This analysis suggests that the food movement, compared to other great social movements of the 20th Century (such as the labour, environment, civil rights, climate and feminist movements), has many of their strengths but not their weaknesses.

Further, the food movement is unexpectedly radical on account of having a distinct philosophy. This philosophy is fundamentally unique in human history and is the underlying explanation for the explosion of the food movement.

Like any significant novel philosophy, that of the food movement challenges the dominant thought patterns of its day and threatens the political and economic structures built on them. Specifically, the food movement’s philosophy exposes longstanding weaknesses in the ideas underpinning Western political establishments. In the simplest terms possible, the opposite of neoliberal ideology is not communism or socialism, it is the food movement.

The reason is that, unlike other systems of thought, food movement philosophy is based on a biological understanding of the world. While neoliberalism and socialism are ideologies, the food movement is concerned with erasing (at least so far as is possible) all ideologies because all ideologies are, at bottom, impediments to an accurate understanding of the world and the universe.

By replacing them with an understanding based on pure biology, the food movement is therefore in a position to supply what our society lacks: mechanisms to align human needs with the needs of ecosystems and habitats.

The philosophy of the food movement even goes further, by recognising that our planetary problems and our social problems are really the same problem. The food movement therefore represents the beginnings of a historic ecological and social shift that will transform our relationships with each other and with the natural world.

1) The food movement is a leaderless movement

The first important piece of the food puzzle is to note that the food movement has no formal leaders. Its most famous members are individuals. Frances Moore Lappé, Joel Salatin, José Bové, Vandana Shiva, Wendell Berry, Michael Pollan, Jamie Oliver, and many others, are leaders only in the sense of being thought-leaders. Unlike most leaders, including of the environment movement, or the labour movement, or the climate movement, they have all attained visibility through popular acclaim and respect for their personal deeds, their writings, or their insights. Not one of them leads in any of the conventional senses of setting goals, giving orders, deciding tactics, or standing for high office. They are neither bureaucrats nor power-brokers, but leaders in the Confucian sense of being examples and inspirations. It is a remarkable and unprecedented characteristic that the food movement is a social movement that is organic and anarchic. This not to argue it is unstructured, far from it. Rather, the food movement is self-organised. It is a food swarm and absence of formal leadership is not a sign of weakness but of strength.

2) The food movement is a grassroots movement

A second and complementary piece of the puzzle is that the food movement is far more inclusive than other social movements. It is composed of the urban and the rural, the rich and the poor, of amateurs and experts, of home cooks and celebrity chefs, farmers and gardeners, parents and writers, the employed and the unemployed. Essentially anyone, in any walk of life, can contribute, learn or benefit. Most do all three. Importantly too, just about any skill level or contribution can often be accommodated. To take just one example, in how many other social movements can a 14-year-old make an international splash?

This inclusiveness has various aspects that contribute significantly to its success. The first of these is that, unlike many protests, there is no upper limit to membership of the food movement. It is not defined in opposition to anything – it would include the whole world if it could – and so there is no essential sense in which it is exclusive. Exclusivity is often the Achilles heel of social movements, but though its opponents have tried to label it as elitist, for good reasons they have not succeeded. Granted, Prince Charles is a very enthusiastic member, but so too are rappers from Oakland, the landless peasant movement of Brazil, the instigators of the Mexican soda tax and the urban agriculture movements of Detroit, Chicago and Cleveland. Such groups are neither elite nor elitist. A better analysis would conclude that anyone can find space under its broad umbrella because the food movement does not discriminate on any grounds, least of all class. It is beyond grassroots. People see what they want in it because it is for everyone.

The second aspect of its inclusivity is that the food movement has barriers to entry that are low or non-existent. This is an important reason it has grown rapidly. These porous boundaries make the food movement unusually hard to define, however, leading some people to mistakenly conclude it is non-existent.

3) The food movement is international

A third unconventional attribute of the food movement is to be international and multilingual. In each locality it assumes different forms. The Campaign for Real Ale, Via Campesina, the Zapatistas, Slow Food and Europe’s anti-GMO movement are very different, but instead of competing or quarreling, there are remarkable overlaps of purpose and vision between the parts. This was on show at last winter’s British Oxford Real Farming Conference where food producers and good food advocates from all over the world shared stages and perspectives and the effect was to complement and inspire each other.

4) The food movement is low-budget

The fourth distinguishing characteristic of the food movement is that it has little money behind it. It might seem natural for “social movements” to be unfunded but it is in fact very rare. The climate movement has Tom Steyer, the Tea Party has the Koch brothers, Adolf Hitler’s car, chauffeur, private secretary, and of course his blackshirts, were funded by Fritz Thyssen, Henry Ford, and some of the wealthiest people in Germany. Even the labour and environment movements have dues or wealthy backers. The food movement therefore is highly unusual in owing little to philanthropic foundations or billionaire backers. Instead, it consists overwhelmingly of amateurs, individuals and small groups and whatever money they possess has followed and not led them. This is yet another powerful indication that the food movement is spontaneous, vigorous and internally driven.

5) A movement of many values

Most social movements are organised around core values: civil rights, social equality or respect for nature are common ones. What is unique about the food movement is that it has multiple values. They include human health concerns, animal welfare, agricultural sustainability, ecological sustainability, food justice and political empowerment, but even this list does not adequately capture the range of its concerns. It is a movement with many component parts.

Explaining the philosophy and synergy of the food movement

For an emergent social movement to have such unique and seemingly unconnected properties suggests the possibility of a deep explanation, and in fact there is one: the food movement embodies a profound philosophical shift.

The narrative dominating international food policy, especially post-1945, has been that food is a commodity (when it is not a weapon) and agriculture is a business. According to this narrative, neither have much to do with the environment or your health. This economic and depleted conceptualisation of food is an ideological extension of the current dominant Western philosophy, which is that of the European enlightenment. The chief character of this philosophy is to be atomistic and mechanistic, meaning that in the formal and official worlds of business, government, the law, education, etc., phenomena are presumed unconnected until proven otherwise, which usually means proven by science.

The evidence for this mindset is ubiquitous. The separation of government ministries: Health from Agriculture and both being distinct from Environment. The reduction of food to the status of an industrial raw material completely measurable by yield or profit is another. The same ideology also allows, in the United States, the agriculture “industry” to be exempt from most anti-pollution legislation, and doctors not to be educated in nutrition. The privileging of the health requirements and food needs of one species (humans) – and usually just a few of those – above that of all other organisms – is a fourth data point.

Citizens in “modern” nations are thus surrounded in everyday life by institutions and practices whose founding rationale is the ideology of disconnection. Thanks to our education, we come to see this state of mind as natural – even though it came into being quite recently – and also inevitable, even though until recently it was unique to Western society.

In contrast, the food movement believes in something very different, which can be summarised as follows: that the purpose of life is health and that the optimal and most just way to attain human health is to maximise the health of all organisms, with the most effective way to do that being through food.

This belief system is derived from practical experience. The food movement has internalised certain observations: the potential of compost to improve crop growth and soil function, the human health benefits of a varied diet, the successes of numerous farming systems in the absence of synthetic inputs, these are a few of those. It also has noted apparent powerful connections between health, agriculture, animal welfare and the environment. These connections allow for the existence of a virtuous circle in which the most ecologically healthy farms generate foods that are the healthiest and the tastiest. These farms are also the most productive. For US examples see here: and for an example from rice see here.

Except for the obviously subjective ones (like taste), there is nothing unscientific about these claims.

We are familiar with the neo-Darwinist narrative of life-as-competition, but this slugfest interpretation hides a bigger and more important truth about life: that before there can be competition, there must first be at least two organisms. Life can, and often does, exist without competition, but competition cannot exist without life. In other words, the neo-Darwinist vision is wrong in that it trivialises biology. Food philosophy replaces this view with the idea that life thrives in the presence of other life. There is perfectly good evidence for this – we know, for example, that all of the tens of millions of species on earth are interdependent. Not a single species could exist if the others were removed. For example, plants and algae excrete oxygen, which all animals need. Animals eat plants and algae, but excrete nitrogen and phosphorus, which all plants and algae need.

Similarly, at the level of individuals, if we can look past the standard mechanistic view of biology offered by celebrated scientists like neo-Darwinist Richard Dawkins, who famously called organisms “lumbering robots”, we can note that all biological organisms are in fact self-optimising and self-repairing systems. They therefore tend to maximise their own robustness and health unless, as unfortunately but commonly occurs, they are actively prevented from doing so (e.g. by a limited environment or a deficient diet).

So food philosophy envisions life in an entirely novel way. There is quite a difference between seeing nature, as the self-styled biological rationalists like to portray it, as robots slowly succumbing to the teeth and claws of vicious nature in comparison to the food view of primarily mutually beneficial interactions between vibrant and dynamic systems. The unfortunate truth for the supposed rationalists is that, as recent research into the microbiome is showing, the food philosophy view better fits the facts than does the neo-Darwinist one. Prisoners of their enlightenment ideology, the neo-Darwinists have turned the message of life on its head.

The origins of food philosophy

Food philosophy has three notable antecedents. One is philosopher Peter Singer’s famous anti-speciesist argument from his book Animal Liberation: that humans have a duty of care towards all animals, with the crucial difference being that the food movement extends Singer’s argument to all organisms, not just animals.

The second antecedent is Gaia theory which proposes that life forms create and enhance their own living conditions. The main difference being that food philosophy applies this thesis to every scale, notably to soils and to landscapes.

The third is Barry Commoner and his four laws of ecology. His second and third laws are consistent with food philosophy. However, Commoner’s First law: “Everything is connected to everything else”, needs modification. The reason is that all things are not connected equally – most connections occur primarily through food. Commoner’s fourth law, which states “There is no such thing as a free lunch”, is flatly contradicted by the virtuous circle of the food movement. All ecological systems generate synergies and synergies between organisms are free lunches; which is why, excepting occasional shocks like meteor impacts, species diversity and biological productivity on earth have continuously risen over aeons.

Like every philosophy, food philosophy implies practical consequences. It becomes the task of a food system, or any sub-part of it – such as a farm – to maximise the positive aspects of each component, so that the circle can become ever more virtuous. By the same token, the food movement believes in the existence of a downward spiral – biological impoverishments such as those that result in dust bowls. Such negative possibilities could be safely ignored were it not the case that many governments and certain businesses seem determined, even enthusiastic, to plunge headlong into them.

Food philosophy therefore represents a major split from post-enlightenment philosophy in its vision of life and biology – which for most practical purposes represents the universe we live in. In so doing it highlights how much the enlightenment was not so enlightened. Enlightenment philosophers used the foundational statement “I think therefore I am” as the justification for effectively disregarding all previous thought. They then adopted the premise that only the tools of logic and deductive reasoning could extend this thought and tell us how to achieve true knowledge and spend our time. But this core presumption was wrong. As the influential philosopher of science, Paul Feyerabend put it, enlightenment ideas are “philosophical tumours” that exemplify “the poverty of abstract philosophical reasoning”.

Food philosophy is thus in the pre-enlightenment tradition of principles deduced from real world experience. It doesn’t ask: what does rational thought reveal about how we should live. It asks: what does nature reveal about how we should live? This is why food philosophy is not a different ideology from neoliberalism or communism; rather, it is the absence of ideology. So while neoliberalism and communism and socialism are products of the enlightenment, food philosophy is not, because it gathers its evidence as directly as possible from the natural world.

To the extent it can be simplified, we might summarise food philosophy approximately as follows:

1) biological interactions allow synergisms of individual health and system productivity, which can be taken advantage of in good farming; and,

2) these biological interactions occur primarily through food, which represents the chemical energy running through the system.

This philosophy is significant in two ways. First, it explains, in general, the form, structure, and composition of the food movement.

Secondly, it predicts the likely impact of the food movement on the food system and society as a whole.

Implications of food philosophy for the food movement

The distinctive features of the food movement can be seen to stem from this philosophy.

The first feature explained by its philosophy is the self-organising and leaderless nature of the food movement. Its members act as if they were reading from an invisible script, which in a sense they are. It also goes far in explaining the lack of money. The philosophy generates values and values are often the most powerful long term motivator of human behaviour.

The attitudes of the food movement also reflect the philosophy. Since the philosophy (see points 1) and 2) above) is universal, constructive, inclusive, flexible, and non-violent, so is the movement.

To take a more detailed example, whereas people outside of the food movement (with their enlightenment hats on) tend to see the issues of human health, food quality, animal welfare, and ecological and agricultural sustainability as concerns to be solved separately (if at all), those inside food movement are likely to see them as connected and therefore insoluble except together.

As people begin to sees these issues as connected, those who enter the orbit of the food movement are likely to move deeper into it. Someone who begins by buying free range eggs, perhaps for reasons of ethics, moves on to keeping chickens and perhaps to sourcing other meats more ethically or more locally. People attracted to flavourful meat or produce are likely to expand their interests into animal welfare or become locavores, and so on. This is why the food movement is deepening and growing.

This same reasoning around the connectedness of food issues also creates an important presumption: that anyone who advances one of these goals automatically advances the rest. Consequently, alliances between individuals and between organisations are likely to form around the common goals, and so the food movement emerges as a synergy between issues formerly identified as distinct, channeling a vast reservoir of positive social energy in consistent directions.

These are explanations for formation and growth of the social movement, but the food movement does not exist for its own sake; like any social movement, it aspires to solve society-sized problems. When the food movement tackles an issue, the features noted above can become enormous assets.

There is usually no actual decision (because typically there is no leader), instead, the philosophy leads its members to use whatever resources are at hand in the most appropriate manner. They develop arguments, write letters, make calls, avoid products, share information, and so on, wherever they perceive the need or opportunity to be greatest, just as the workers of an ant or bee colony do whatever job appears in front of them without explicit orders. To the multinational corporations who are its targets, movement activity may feel like a piranha feeding frenzy. Blood is scented; arguments are sharpened; protests register on social media; more attackers arrive; the target howls; opportunistic journalists pile in; maybe some legislators too, until finally the target agrees to amend, label, or remove the offending product, ingredient or publication. These are food swarms, and they are what direct democracy looks like.

Following once again its own philosophy, food is also a guide to action. Using its enlightenment rationalisations, a government can instruct people, for example, that irradiated or GMO food is safe to eat. But it cannot make them eat it. Resistance based on food logic is always likely to beat enlightenment logic when the subject is food, because it is both rational and relatively easy for the people to both form their own opinions and spend their money elsewhere. The food system is perhaps the one domain where the people retain this power, certainly more than they do in any other domain of public life.

In consequence, time and again the arguments of the food movement: over GMO safety, the benefits of organic food, the dangers of antibiotics in animal farming, food additives, GMO labeling, and so forth, have gained traction out in the public domain (though not always yet in public policy). The combination of solid logic and practical power is hard to resist. Through its philosophy, therefore, the food movement is succeeding both in building itself and winning practical victories as it does so.

Thus one can begin to see how food issues are the organizing principle for a grand social movement. Indeed, the successes of the food movement are now sufficiently evident that major parts of the old environment movement, plus the health and wellness movements, and even parts of the labour movement, have begun to reframe their activities as coming from a food system perspective. Some have largely migrated into the food movement altogether. For example, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers is much better known to the public and has been more successful through its food connections than through its union ones. To a significant degree, once separate social movements are converging to become branches of the food movement.

We can sum up this rather complex state of affairs by saying that food is a highly successful rallying point. It serves well because food is simultaneously a novel conceptual framing for much of human affairs that is strongly distinct from the standard enlightenment framings of economics and social Darwinism, but also because it acts as a potent organising principle for individuals to act around. Food succeeds as a conceptual framing because it is simultaneously anthropocentric and truthful, and it succeeds as an organising principle because food fruitfully highlights the practical biophysical linkages between issues. So while most frames are artificial mental constructs that have zero underlying biological or physical substance, the frame used by the food movement also precisely reflects the key biological reality that a universal daily requirement of all humanity, is food. Good food. And the same is true for other species. Thus, our good food also needs good food, and so on ad (almost) infinitum. Anyone who adopts that devastating logic has a huge advantage, not only in understanding how the world really works, but also in acting on that information.

How will the food movement impact society?

Ideas are the currency of power. Philosopher Peter Singer wrote the book Animal Liberation in 1975. It spawned the international animal rights movement and drove society-wide debates on the human usage of animals for research and in agriculture. Forty years later, the increasing popularity of veganism shows his ideas are still gathering momentum. Singer’s achievement was to show that enlightenment thinkers had attempted to rationalise – rather than ditch – the concept of human exceptionalism, which dated back at least to the Bible’s authorisation of Man’s dominion over the earth. At a stroke, Singer destroyed the arguments for treating animals badly and provided a perfect example of how enlightenment rationalisations have functioned to constrain modern thought, and most particularly the human potential to do good.

Because they go far beyond our treatment of sentient animals and extend to all organisms, the ideas of food philosophy are significantly more profound and far-reaching than those of Peter Singer. Food philosophy is an intellectual key to overthrowing mechanistic reductionist society. Much of standard economics, large parts of biology such as neo-Darwinism (selfish genes) and genetic determinism, reductionist biology and medicine, which at present are the centrepieces of Western education, will come to be seen in their proper light, which is as largely irrelevant to the functioning of whole systems. These are the “philosophical tumours” that stand in the way of human development. To the many individuals who suspect that enlightenment thought is the engine driving our societies over an ecological cliff, food philosophy offers the conceptual way out.

Enlightenment thought arose in tandem with industrialising societies. Enlightenment thinkers laid the groundwork for a meritocratic and commercial society to replace feudalism, but the grand irony is that they did not themselves gain acceptance solely on merit. Rather, they were selected for their usefulness. Their ideas justified the necessary concepts the new society came to rely on: mechanisation, individualism, and competition. Enlightenment philosophers were largely establishment figures giving form to establishment thought. Nowadays their ideas are used for preserving this order, but since the intellectual flaws of that understanding are increasingly manifesting as ecological crisis and social disorder, the same process is happening in reverse.

But the question has long been what will take their place? As I was completing this essay I consulted The History of Western Philosophy by Bertrand Russell. Even in 1946, Russell saw that a satisfactory philosophical resolution to the problem of how to reconcile power and the benefits of social cohesion with individual liberty was yet to be reached. At the very end of introducing modern philosophy he writes that the scientific enterprise tips the balance towards power, but is itself “a form of madness” in that it prioritises means over ends. Without a philosophical antidote this imbalance will become “dangerous”. He concludes “To achieve this a new philosophy will be needed”.

Enlightenment ideas have been developing for almost 400 years. They are largely mistaken, but they were also mistaken when they were conceived. There are two good reasons why no overhaul took place, even at the heights of the social movements of the 1960s or the environment movement in the 1970s. The first is that no adequate philosophical replacement was available. The second is nakedly political. No political force or social movement was previously in place to force the issue. The food movement, however, fulfills both requirements, and so the pieces are finally in place for a peaceful social revolution of thought and action.

The final analysis

This essay has attempted to understand how and why a successful social movement can arise, and even be called a social movement, when it lacks essentially all of the traditional props and attributes of social movements – strong leadership, organisational structures, formal outreach programs, money, and so forth.

This analysis attributes the success of the food movement largely to factors internal to itself. Its members share an infectious vision which is constructive, convivial, classless, raceless, international, and which embraces the whole world. That vision rests on a novel and harmonious philosophy. It is also deeply realistic because it is biological in nature; so while the remainder of society is naively getting further out of touch with the natural world by adopting ever fancier communications devices, internet apps, high speed travel, Pokemon Go, and so forth, the food movement is busy getting in touch with that world and being successful in working with it.

One issue largely missing from this analysis, however, is the imperative of confronting climate change. The food movement did not come together to solve this issue. Nevertheless, many in the food movement believe it has the tools to largely solve the problem. The reasons are simple. First, perhaps as much as 50% of all greenhouse gas emissions result from the activities of the industrial food sector. Secondly, carbon can easily be removed from the air and stored in soil and in the process creating the type of soil actively desired by organic and agroecological farmers. These farmers are still developing their techniques for carbon sequestration, but anecdotal evidence suggests that soil sequestration can combine with food production to store many tons of carbon per acre per year. Thus, as two recent reports show, the food system desired by the food movement can make our atmospheric carbon problem manageable and perhaps solve it completely.

This information seems not to have penetrated the mainstream climate movement. Climate leaders seem to believe solutions must be technical or social: but windmills, solar power, electric cars, dams, divestment, infrastructure protests, etc., are largely symbolic actions. Unlike reducing demand for energy by reforming and localising the food system or storing carbon in living soils, such “solutions” do not necessarily reduce overall use of fossil fuels nor prevent the release of greenhouse gases from disturbed ecosystems. Worse, as resource-intensive ways of generating and storing energy, technofix solutions have many negative consequences of their own.

Hopefully sooner, rather than later, the well-meaning but misled climate movement will come to understand the (typically enlightenment) error of singling out specific forms of pollution (CO2 or methane) and join with the food liberation movement. If not, the food movement may solve climate change without them.

In the ultimate analysis, the growth of the food movement is the people’s response to the failing ideas of the enlightenment. It represents a tectonic realignment of the forces underlying our society and a clash of ideas more profound than anything seen since the collapse of feudalism and the emergence of the industrial revolution. The outcome of this clash will determine not only the future of our society, but also whether our descendents get to live on a planet recognisable to us today. The portents are excellent. The food movement is prevailing because it takes advantage of the synergies and potentials inherent in biological systems, whereas the ideas of the enlightenment ignore, deny, and suppress these potentialities. It will indeed be a beautiful struggle to turn these portents into reality.

Original Post

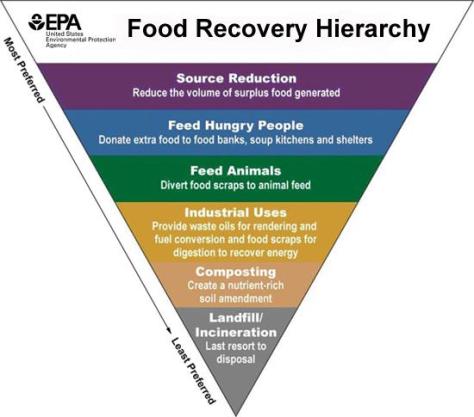

This course is an introduction to food waste, and the impact waste has on our food system. We will introduces the current food recovery hierarchy, and examines how consumers, producers and distributors waste food. We will explore the environmental and social impact of food waste in our food system, and introduce social and policy initiatives employed to recover food. Students will read, reflect and discuss the actionable steps being taken to shift our local food system’s food waste into food recovery.

This course is an introduction to food waste, and the impact waste has on our food system. We will introduces the current food recovery hierarchy, and examines how consumers, producers and distributors waste food. We will explore the environmental and social impact of food waste in our food system, and introduce social and policy initiatives employed to recover food. Students will read, reflect and discuss the actionable steps being taken to shift our local food system’s food waste into food recovery.

Food waste can be turned into organic fertilizer. (Flickr/EarthFix)

Food waste can be turned into organic fertilizer. (Flickr/EarthFix)